What problem or challenge are you currently working to address?

I’d say, I have spent about the last thirteen years trying to solve the issue of globally inequitable access to the medicines. Generally, my work was linked to two issues: one, the high prices of medicines, and two, the way the current research and development system for medicines functions, which does not prioritize unprofitable diseases. But the problem that I have been more recently started to engage with, is that health is insufficiently protected in global governance systems. It’s a different problem, but I also see it as a different way of looking at the same problem.

Who or what inspired you to take the path you took?

I think my overall interest in health and the issue of access to medicines comes out of a real sense of shock about the way in which most people on this planet live. And trying to understand, why is that? What are all the systems that contribute to the fact that a baby born in a certain country has such different life chances from a baby born in this country? Trying to figure out, how do you remedy these huge inequalities that we see in the world today? Health is one aspect in which we see a manifestation of these massive inequalities. But, I think, being exposed to extreme poverty, seeing it first-hand, really struck me. The first time I saw it was in rural Mexico when I was a high school student. Seeing the huge difference between rural Mexico and southern California, which is where I was in high school, was something that stuck with me.

And, how does that lead to global governance? The middle step was working on this access to medicines issue, which was very much about what happens when you have massive inequalities in the global trade system. I learned from working on access to medicines, and in particular by understanding the trade system and how intellectual property rules work, that it is one symptom or manifestation of problems with the global system in general. That was kind of the natural progression of moving from the issue of access to medicines to this broader, and somehow more abstract, issue of global governance.

Give a sampling of the work you do on a day-to-day basis.

In some ways I feel lucky because I’m very interested in the work that I get to do. In other senses it doesn’t sound so interesting because I spend a lot of my time sending e-mails, teleconferencing with people, and traveling. Lots of trains, planes, automobiles, and going to meetings. That is what I do today, but in the past, I spent more of my time, doing a bit more hands on work. Now, like a lot of people who are at that nexus of academia and policy probably, I spend a lot of time corresponding. Of course, on good days, and on other days, I do a lot of research, writing, and thinking.

When I work with my academic hat on, I work with students, other faculty, and researchers at other academic institutions. But wearing my policy hat, I work with a lot of civil society organizations, activists, journalists, government officials, and people who are staff at WHO, the Global Fund, or other big international institutions. It is a fascinating to get to work with such a broad range of people, and different, depending on which hat I happen to be wearing.

What are the enjoyable parts of your work? What are the less enjoyable parts?

I definitely enjoy getting to work with a really broad range of people at all different stages of their careers and lives. Working with people from different countries is fascinating. It’s a privilege and a constant sort of source of growth. And I like it when I have the chance to read and reflect and write. Writing is painful for everyone, even for the best writers, but I like that process, and that I have the chance to do that with this work.

I don’t like spending all morning on e-mail. And in this day and age, a lot of us spend a lot of time doing that. I don’t like the nuts-and-bolts work that has to get done – the administrative stuff. And I really don’t like petty politics. I find that a huge waste of energy and time, but unfortunately, that is everywhere.

What is a challenge that you have faced in your career? How did you deal with that challenge?

One of the challenges is that there is not a clear track for me. It’s not a career that moves in a very defined and clear way from step A to step B to step C to step D. There are a number of careers like that. In medicine, or law, for example, often times there is a very clear progression. Or at big organizations, like the World Bank: if you stay within them, they tend to have very clear tracks for a good reason. I’ve chosen not to do that. That gives you a lot of freedom. If you don’t feel confined to a track, you don’t feel confined to a track. On the other hand, it also leads to a lot of uncertainty and you are never kind of sure where to I go next. What does that mean to progress in your career? It’s not necessarily moving from an assistant to an associate position, which is sort of a standard progression in a lot of bureaucracies or large organizations, I should say. But it does allow me to pick and choose problems that I want to work on and take different opportunities as they come up. Freedom usually does come with a bit of risk. It’s riskier in some ways if the end goal is to achieve a certain position because then it’s not clear if I will ever get to such a position. But, if the end goal is something else, which is to do interesting work that I think makes a difference and is meaningful to me, then it’s not a bad way to go.

And how do you decide when to move onto something different? One clear criteria, if I look back at when I’ve moved on, has been when the opportunity to grow has stopped. That can happen for lots of different reasons. Either your boss doesn’t help you to grow, or the organization that you are in does not allow to you grow. Or sometimes it is timing. Maybe it has nothing to do with the organization or the boss. It’s just where you’ve ended up. I think that feeling of bumping your head against the wall, or the ceiling, or whatever the barrier may be, when you feel like you’re not moving and you’re not growing – that’s a good moment at which to move on.

What types of interests and activities do you maintain outside of your work?

Yes, it’s important to do things outside of work! I love to cook, and garden, and eat. Kind of one theme there: food. Food is very important to me. I love to travel for fun, and it’s great to combine that with my work. I get to travel quite a bit for work, both to project sites, where you see a lot of direct service activities happening, as well as conferences where you generally sit in a hotel room the whole time and sometimes you don’t even know which country you are in, which is terrible. The great this is, usually then, you take time after the meeting is over, you might be able to take a few days or a week to travel around the area that you’ve been invited to for a conference. That’s great. I also love to meditate. Meditation is one of the most important and balancing and grounding things that I’ve learned to do in the last few years. And yeah, spend times with friends and family, I think everyone likes to do that.

Can you recommend pieces of media that profoundly shaped you?

– I love Amartya Sen’s book Development as Freedom. It changed the way I thought about development, and what does it mean to try to improve life for some of the poorest people on the planet. What does that actually mean? I give that book to a lot of people. So many, wow.

– Thinkers! Maybe not books, but thinkers who’s writing I found really influential: Gandhi’s writing on non-violence is really amazing and wise, and is inked very closely to the philosophy of civil disobedience.

– The idea of activism, too. I love stories of social campaigns. Charles Tilly and Sidney Tarrow have written books about social movements and social change throughout the centuries, so I would recommend their work.

– Okay, now you’ve got me on a role. I’m a huge fan of Dani Rodrik’s work and he’s just come out with the new book, The Globalization Paradox. That is a super interesting book.

– Joe Stiglitz’s writing, I am a fan of. It is sort of a critique of globalization and the idea that unequal globalization is not good for anyone. That we need to find ways of better managing globalization to make it more humane. That sort of stuff I like. That’s more than two or three.

What advice do you have for people in their early stages of exploring?

One is to spend time in the field, quote on quote. What do I mean in the field? It doesn’t have to be in another country, but engaging in work in the communities and with the people who you are trying to help in a way. That can be in the United States, in another country, or even in your backyard. Students should absolutely take the time to see the problem first hand and see how people live. A lot of people do that over the summer. If you the opportunity to do that – that’s great. But there’s something about spending a bit more than a few months on the ground. And spending at least a year, and seeing, through the cycle of a year, what people not only go through, but how resilient people can be in dealing with challenges. It can be health. It can be other situations. Many of us, who have the privilege of coming to places like Harvard, or Yale where I went to college, come from very privileged backgrounds, certainly compared to the world at large. Not all of us, some come from very under-privileged backgrounds, but compared to the majority of the 7 billion people on this planet, we are extremely privileged. And to try to work on global health or social justice issues, you really need to try to understand what it is that people go through on a day-to-day basis.

Two is, for people who can tolerate the uncertainty, to explore paths that are not on the track. That doesn’t mean that you should never be on the track, but you should not be afraid of taking a step off the track. I know a lot of people, who do really interesting or rewarding work today, and got there because they were willing to take a step off the track. Again, coming from a place like Harvard, there is often pressure to get onto a track, stay on that, and to achieve success that is defined in a very conventional way. I don’t think that is always the way to discover your passion or find work that you consider meaningful. Sometimes it is. But sometimes it’s not.

And the third is to talk to lots of people, and learn as much as you can from other people’s experiences: what they’ve done, what they’ve liked and didn’t like, and why. That is a great strategy: to just expose yourself to as much as you can.

What is your vision for the problem or challenge you are working to address?

I think we need to ensure more equitable access to medicines, and I don’t think in my lifetime, or even in your lifetime we are going to see that perfect world where everybody always gets what they need, but we can move a lot closer to that. We need much stronger formal institutions, by which I mean stronger laws at both the international and national level. Right now we are relying on a sort of hodge-podge of soft norms and voluntary agreements. It’s just unpredictable gestures of charity, and it’s not enough. We need to move to stronger, more predictable systems at the global level that ensure that people’s right to health is protected. There is a proposal on the table right now for a treaty that is trying to reshape the global system that shapes research and development of new medicines. That’s the type of system that we need to be moving towards, but it will take us a while to get there, if we get there.

On global governance, I can describe what a better system would look like. How we get there is rather murky (laughs). One way of thinking about it is a system that tries to approximate a global democracy. The voice of one person, regardless of which country they come from, how rich or poor they are, their gender or their race, should be politically equal to the voice of any other person. That is the bedrock principle behind democracy. We don’t have that at all at the global level. We’re nowhere close to that. So how do we move to a system like that where everybody’s rights are equally weighed in decision-making? Is that possible to achieve? I don’t know (laughs). I don’t know.

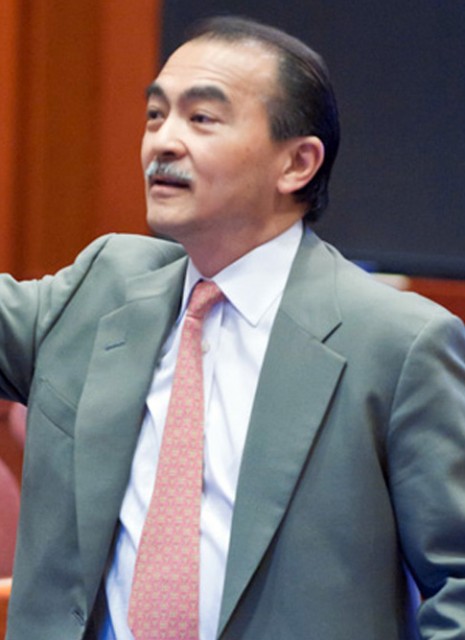

| 2 | Suerie Moon 1 - What problem are you currently working to solve? |

| 3 | Suerie Moon 4 - Who or what inspired you to take the path you took? |

| 4 | Suerie Moon 5 - Give a sampling of what you do on a day-to-day basis. What types of people do you work with How does your work continue to you challenge you. |

| 5 | Suerie Moon 6 - What are some of the enjoyable parts of what you do What are some of the downsides of what you do? |

| 6 | Suerie Moon 7 - What is a challenge that you faced in your career How did you deal with this challenge? |

| 7 | Suerie Moon 9 - What types of interests and activities do you maintain outside of your work? |

| 8 | Suerie Moon 10 - Can you recommend three articles or books that positively impacted you that students might benefit from reading? |

| 9 | Suerie Moon 11 - What piece of advice do you have for students who are in the process of discovering their passion? |